Your donation sets the stage for a new season of Boston's most intimate, entertaining and provocative plays and musicals. Our shows make powerful connections with our audiences-- and they are only possible because of you.

Bloody Bloody Hard Work

Bloody Bloody Hard Work

Bloody Bloody Hard Work

Sometimes, ideas happen easily. Get the right personalities and ingredients together, and a concept can emerge seemingly from thin air. Case in point: it only took one coffee-shop discussion for Alex Timbers and Michael Friedman to settle on a concept for what would become Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson. It was a moment of sublime serendipity, particularly considering that they’d never even met before their, as they term it, “artistic blind date.” But the idea is only the first step of a play’s journey, particularly when it’s an idea as crazy as an emo retelling of the life of our nation’s seventh president. Getting from the coffee shop to Broadway was a four-year long, bi-coastal journey requiring a vast array of collaborators, a significant amount of risk, and a near-constant sensitivity to both history and the changing political climate in which the show lived.

The first stop on the road came in August 2006, when Timbers and Friedman brought the first section of their script and a handful of songs to the Williamstown Theatre Conference, to begin shaping it. Timbers had been invited by the festival’s directors to workshop a new piece with a company of non-union actors, and he and Friedman took the opportunity to hammer out the basic experience of Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson. Over the weeks they spent working, the show gradually developed more length, more structure, and more songs. The rehearsal process put an emphasis on collaboration, not just between Timbers and Friedman, but between everyone involved, including the actors, designers, and musicians. It was an anarchic approach for an anarchic idea, and the results were a spirited, controlled chaos with plenty of attitude and lots of room for experimentation. Often, figuring out what a scene needed meant pursuing ideas that came out of left field: the show’s opening number, “Populism, Yea Yea!” got its title and refrain from an off-the-cuff joke Friedman made in a brainstorming session, imagining the lamest, most on-the-nose song name imaginable. Embracing that obviousness and then finding ways to make it surprising became a key to the tone of the piece for all involved.

Friedman and Timbers went into Williamstown hoping to emerge with a full draft of the show, but they came out with even more. Michael Ritchie, the Artistic Director of Los Angeles’ Center Theatre Group, heard a recording of the performance and agreed to produce the piece the next season. They also gained a leading man: Benjamin Walker, whom Friedman was working with on a different Williamstown production during the same period. Walker saw the reading of Bloody Bloody and asked to be considered for the role of Jackson; Timbers and Friedman agreed, and Walker came with them to Los Angeles. (He would end up playing Old Hickory in every workshop and production for the next three years.)

When Bloody Bloody reached the West Coast, the structure of the play was in place, but its politics were still very much in flux. For one thing, the history kept changing: new books and research and ruminations on Jackson were coming out constantly, and each audience seemed to have a different perspective on the show’s protagonist. All this information influenced the tone of the play, and led to a darker, more contemplative second half amidst all the humor.

The show’s modern connections were growing, as well. Timbers and Friedman had originally envisioned the character of Jackson as a jab at then-president George W. Bush, but realized early on that Jackson’s story could be used to illuminate just about any politician of the modern era. The more that they workshopped, the more they sharpened and opened up the satire, eventually using the buzz surrounding the LA production to bring the show back to New York, in a workshop at the Public Theatre that went into previews in the middle of the 2010 battle over health care. With Tea Partiers in the street and a sitting President who had been elected on a platform of populist energy, Timbers and Friedman had brought their show to the stage at the perfect time to join the conversation. The Public Theater production was extended, then moved to the mainstage, and ultimately made the transition to Broadway’s Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre. It had been a long journey from a coffee shop four years prior, but the central idea was still there, resonating even more than it had when it had first emerged.

—by Walt McGough

Join us for spectacular season 33!

Join us for spectacular season 33! Past Productions

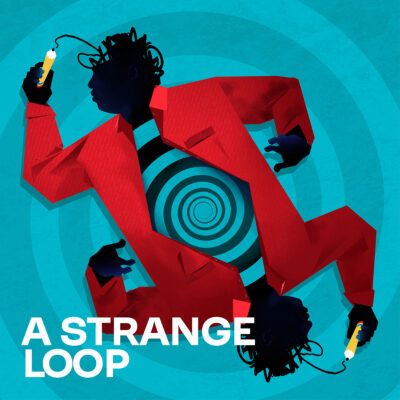

Past Productions a strange loop

a strange loop